HOW TO OPTIMIZE PEOPLE

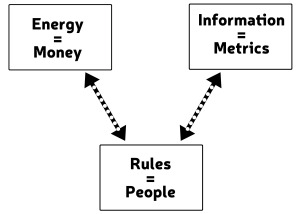

As I’ve explained, an energy and information system is a feedback loop, and the crux of that loop is the rules—where energy and information meet. The rules make it possible for the energy to affect the information and vice versa.

Since the rules in your business are defined by employee behavior, when it comes to optimizing, you should always look to your people first. Influencing employee behavior in positive ways is most likely to result in positive changes throughout the system in the least amount of time and with the least amount of effort.

One of the greatest challenges for business owners is figuring out how to get the best results from their people. But before we can think about the how, we should first focus on figuring out the why. If you know why certain employees are turning up red—or even yellow—in your models, you can make better choices about how to optimize the value of their work to the business.

There are countless reasons why employees might be doing less than optimal work. After all, human beings are complex; each one of your employees is a unique individual with his or her own personality, personal life, psychology, and experiences. What’s more, all of these factors are subject to change over time. A recent grad that has never had a full-time job, for instance, might be under-performing because she lacks confidence. A new employee might not be familiar with the systems particular to your business. Even a long-time employee who has consistently excelled can suddenly start appearing red on the models if, say, he has a new baby who is keeping him up nights, is distracted by a divorce, or has developed a chronic illness.

So, my first word of advice concerning optimization is: Get to know your employees. The better you know what’s going on with your people, the easier it will be for you to help them improve their work. The recent grad might gain confidence from a mentor; the new employee might learn systems better with additional training; the employee of many years might benefit from a flex schedule or a leave of absence.

Getting to know people can also help you correct what I’ve found to be one of the most common causes of under-performance: a mismatch between employee and job function. Investing more time in the hiring process can help you avoid this problem, but an easy fix once it exists is to identify what the employee’s strengths are and reassign them to a position that is a better fit. Your models are a great tool for this sort of thing. Think about it, if you see that the person who writes your press releases is coming up red in every area of their job except for calculating statistics, where they are green, maybe that person would do better in a role focused on numbers. Maybe the accounting department has an opening.

So far, all of these examples have shown how you can change your employee’s circumstances to facilitate optimization. By far, the harder road to optimization is asking employees to change their own behaviors, actions, or attitudes.

If you’re lucky enough to have a staff full of confident, well-trained, well-placed employees who, for whatever reason, came to the job eager to do whatever it takes to achieve maximum results, you’re in a great position for optimizing the value of their contributions. In fact, if they aren’t doing optimal work already, it’s probably because they just don’t know where they need to improve. In this case, you don’t need to do anything but direct them to the places where they are coming up red on the models so they know where to focus their attention.

Chances are good, though, that at least some of your employees never had that innate drive or enthusiasm, or maybe they lost it in the daily grind. Just showing them the red won’t make a difference. So, what is going to make them care enough to change their behavior in a way that will lead to better results?

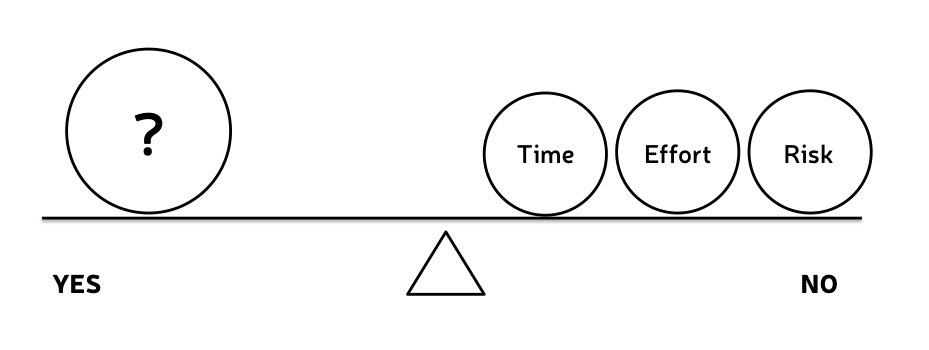

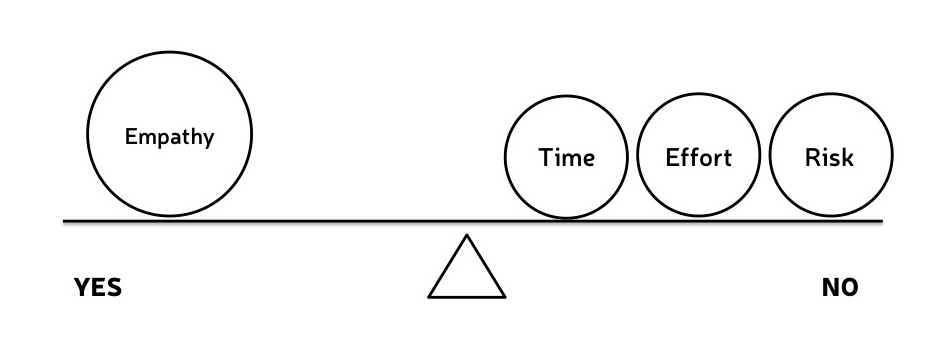

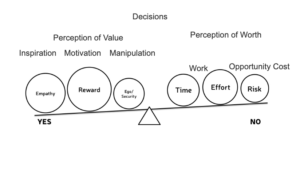

Basically, you are asking that person to put in more time, exert more effort, or accept more risk in order to increase the value of their work. So you need to find a way to make that time, effort, or risk worthwhile, to tip the scale in the illustration below towards “yes”.

I recommend starting out by explaining why it matters. Pull out your models and show people how they are doing, how their work affects the ability of their co-workers to do their jobs, and how their work impacts the overall business. I find that once employees understand their connection to the bigger picture, they are more likely to make better decisions. With better decision-making, the quality and quantity—the value—of their work increases.

However, if showing your employees how they impact the business on a larger scale doesn’t elicit the response you’re looking for, there are plenty of other ways to influence behavior. Below, I’m going to discuss a few general approaches, namely:

- Inspiration

- Motivation

- Manipulation

These are things that I have tried, with varying degrees of success, to get optimal results from my employees. They are by no means the only options and perhaps not the best ones for you. In the end, you should adopt methods that make sense for your employees, as well as your own particular circumstances, goals, philosophies, and management style.

INSPIRATION

For some people, a job is just a job. But many people want a job that gives their life meaning, that makes them feel like they are contributing to something big and important. Those people are looking for inspiration, and when they find it, they are much more likely to want to do their best work. So how do you inspire your employees? You give them a vision to believe in and share.

Back in 2007, I launched a project to collect used laptops through GOT JUNK, and ship them to refugee camps in Africa. I used a map to pinpoint the locations of the camps where the laptops were sent and arranged for the people in Africa to send us pictures of the laptops being used. The program, called Project Red Dot, helped a number of refugees and inspired a lot of employees who felt good about making a difference in the lives of others. (At the same time, it had a positive impact for me. Customers who donated laptops got the satisfaction of seeing pictures of their “junk” in use, and the project, which cost nothing to run, generated tons of free press, which brought in almost $100K in revenue.) It was a stunning success by all measures.

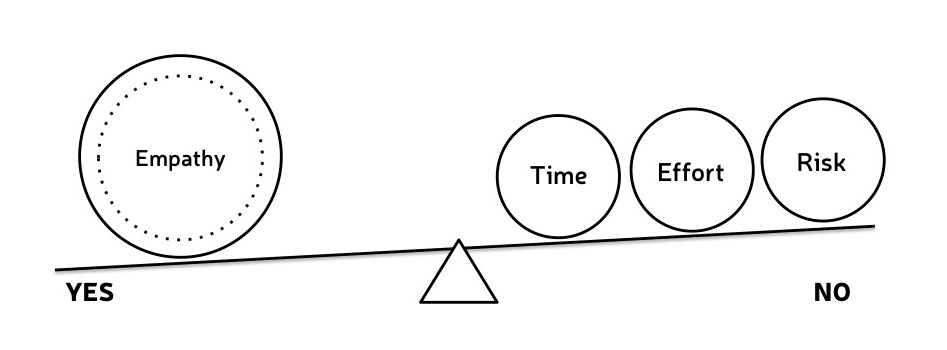

Inspiration is most effective when you are dealing with highly empathetic people who are more inclined to “feel” what you’re feeling. If you’re enthusiastic about something, an empathetic person will pick up on your excitement and be similarly enthused. This makes it easy for you, as the business owner, to spark that person’s passion, give them an emotional connection to their work, and align them with the higher purpose of the company. Of all the ways to change behavior, I prefer inspiration because it creates a powerful and compelling connection—a shared goal—between your people and your business.

In visual terms inspiration works something like this. The degree to which you can appeal to the person’s empathy is weighed against the combined factors of the time, effort, and risk involved in their job.

If a person is inspired enough, they will put in their best effort no matter what the effort, time, and risk. This explains why some people volunteer to provide humanitarian aid in war zones.

If a person is inspired enough, they will put in their best effort no matter what the effort, time, and risk. This explains why some people volunteer to provide humanitarian aid in war zones.

In your business, if you want someone who is indifferent or reluctant to improve their work, an appeal to their empathy—a little inspiration—might be what tips the scales.

With inspiration, the more effort or time you ask someone to put in, or the more risk you ask them to assume, the greater your appeal to that person’s empathetic inclinations will have to be.

MOTIVATION

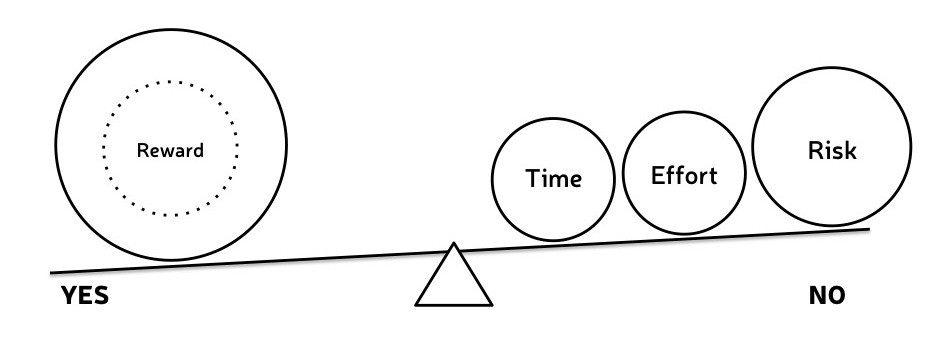

Another strategy for influencing employee behavior and optimizing employee value involves increasing rewards. This is what I refer to as motivation.

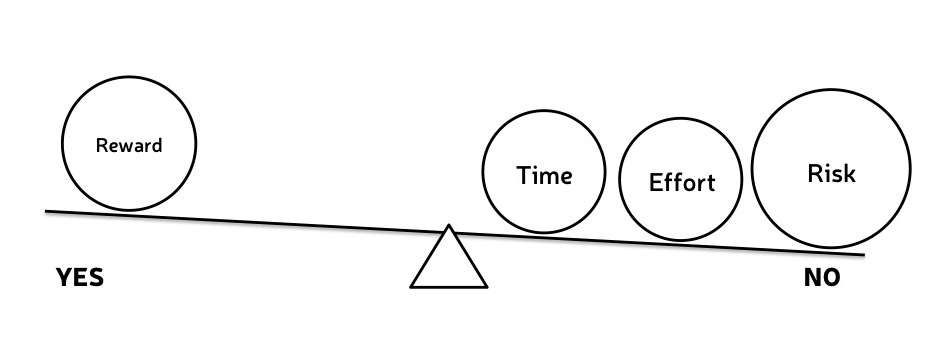

If the rewards are great enough, the employee will be motivated to do the job regardless of time, energy, and risk. This explains why mercenaries, given a large payout, are willing fight and possibly die for a cause they don’t believe in.

The same principle holds for your business. If you want someone to improve their work, (i.e. put in more time or effort, or accept more risk,) you might be able to make that happen by offering greater rewards to tip the balance.

Can I pay you $1 a day to clean up Fukushima? No. It’s too risky.

Can I pay you $1,000,000,000 a day to clean up Fukushima? Yes. It’s worth the risk.

Can I pay you $1,000,000,000 a day to clean up Fukushima? Yes. It’s worth the risk.

Extrinsic motivation, or external rewards, such as promotions, raises, bonuses, certificates, trophies, special events, etc. appeal to the employee’s sense of equity or desire for recognition and material gain, and they can be very useful indeed.

For my junk business, I have an incentive plan to motivate my truck teams to bring in as much revenue as they can in the shortest period of time. Each truck has a laminated copy of the plan in a binder along with the price list. At every job, the truck team estimates how much the job will cost. After that, they have to sell the job to the customers. The more my truck teams charge, the more money they get. For example, if they work 10 hours and bring in $2000, each guy would get an extra $29 for that day. The faster they work and the more revenue they bring in, the bigger their bonus. I had to try a number of different of versions of this plan until I found the optimal one, but eventually I did, and the program is now highly successful.

One caveat here: You do need to be careful when offering external rewards, because they can lead to misalignment between the employee’s goals and the goals of the company. For example, let’s say that you compensate people to provide excellent customer service and bonus them on the results of customer service surveys. You might see a noticeable change for the better in their customer interactions. On the other hand, they might cut corners in other parts of their jobs and concentrate only on those things that will get them better survey results. Your employees end up gaining at the expense of other areas of the business. Here’s another example of the dangers of extrinsic motivation taken from my actual business.

Agents at my call center used to be incentivized with commissions for booking leads on the schedule. A number of agents realized that they could earn their commission by giving a low quote, whether or not that quote was accurate or the lead was qualified. When my guys got onsite and the potential customer realized that the actual pricing was higher than the quote, they would cancel. But the call center agents got their commissions anyway. (At some point, the person who runs the call center figured this out and changed the program. Now, the agent ONLY gets a commission if the lead turns into a paid job. This has ensured that everyone—employees, business, and customer—benefits.)

Clearly, with some fiddling, extrinsic rewards can work to everyone’s mutual benefit. But a safer alternative is internal rewards, or intrinsic motivation, which appeals to a person’s likes and interests. If your employees don’t enjoy their jobs or the work doesn’t interest them, they probably won’t be performing at their best and won’t be motivated to do any better. Moving an employee to a position that interests them or shifting their responsibilities in certain areas so that they are doing more of what they like and less of what they don’t like can make a huge difference. When your employees get personal fulfillment from the work they are doing, they will be motivated to do their best, and you won’t have to worry about accidentally incentivizing them for behavior that is detrimental to their coworkers, your customers, or the overall business.

MANIPULATION

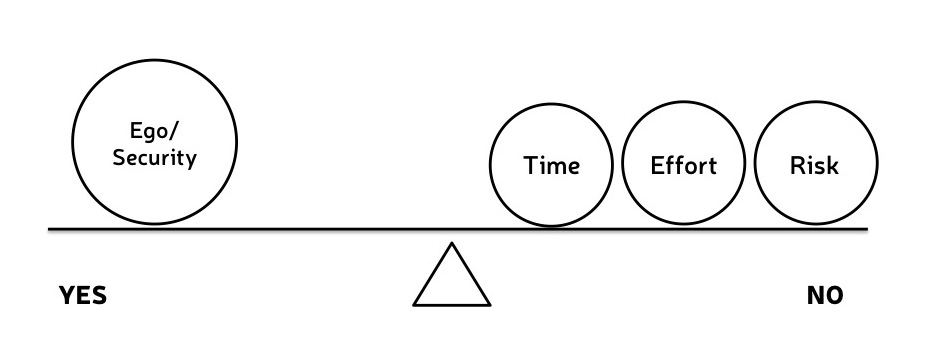

If inspiration appeals to empathy and motivation appeals to the desire for equity or reward (internal or external), manipulation appeals to an individual’s ego and sense of security. Manipulation works best when people are the most insecure. People with low self-esteem, for instance, are easy to exploit because they often respond to manipulation by trying to prove their worth. Likewise, people who are insecure about their jobs may be swayed by threats, such as demotion, pay cuts, or firing, to do more or risk more.

I can’t deny that manipulation can be effective, and if I’m honest, I have to admit that I have used it in the past, although in retrospect I don’t feel very good about it. I don’t like manipulation. Not only does it damage relationships, but it’s also an ineffective long-term optimization solution because it never aligns the goals of the employee with the goals of the company. So it’s not an approach to influencing behavior that I recommend.

I can’t deny that manipulation can be effective, and if I’m honest, I have to admit that I have used it in the past, although in retrospect I don’t feel very good about it. I don’t like manipulation. Not only does it damage relationships, but it’s also an ineffective long-term optimization solution because it never aligns the goals of the employee with the goals of the company. So it’s not an approach to influencing behavior that I recommend.

A much more effective long-term solution, and a more humane one that I do encourage is the opposite of manipulation—building confidence.

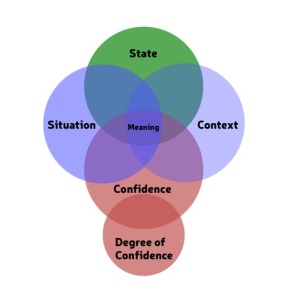

The way I think about it, every experience a person has is comprised of five elements—state, context, situation, confidence, and degree of confidence—which can be visualized like this:

When I refer to state, I mean emotional or psychic state—how is the person feeling, what is their current mindset, are they angry, nervous, excited, etc. Context is the information that defines how they understand what is happening. Situation is the thing that is happening or task at hand. Confidence refers to their level of comfort with the experience. And, finally, degree of confidence is the rate of change of their confidence.

When I refer to state, I mean emotional or psychic state—how is the person feeling, what is their current mindset, are they angry, nervous, excited, etc. Context is the information that defines how they understand what is happening. Situation is the thing that is happening or task at hand. Confidence refers to their level of comfort with the experience. And, finally, degree of confidence is the rate of change of their confidence.

When you manipulate people, what you are really doing is stabilizing the degree of confidence with negative input, bringing about decreased confidence, which then impacts every other part of the experience for the worse. When you seek to stabilize the degree of confidence with positive input, you raise confidence, which makes for a better experience overall. It’s not only rewarding to help people feel confident, it’s a great way to optimize performance, too.

FINDING THE RIGHT BALANCE

As mentioned, no two human beings—employees included—are exactly the same. That means that different people may respond to different methods of influence at different times. And, different people will also respond to different combinations of these approaches. Fortunately, none of the aforementioned methods of influencing behavior is mutually exclusive. It might be that with a little inspiration and a small raise you can get one person to put in more time and effort or take on greater risks. For another person, the key might be building confidence and offering intrinsic motivation. In the end, it’s a balancing act.

If you can’t find the right balance, one that gets the most out of your employee, you might need to go back to your models and reconsider your expectations. Alternatively, you might decide that the best way to optimize is to fire the person and hire someone else in their place.

If you can’t find the right balance, one that gets the most out of your employee, you might need to go back to your models and reconsider your expectations. Alternatively, you might decide that the best way to optimize is to fire the person and hire someone else in their place.

After the people are optimized, the next step is to take a look at the metrics.

- There are countless reasons why the value of an employee’s work might be less than optimal. Some of these factors are controllable; others are not.

- To optimize the value of a given employee’s work, you will likely need to change their behavior.

- An employee’s behavior is based on a balancing act of the effort, time, and risk they are asked to put into their work and what benefits they derive from their work.

- You can usually change an employee’s behavior through inspiration (appealing to their empathy), motivation (appealing to their desire for reward), or manipulation (appealing to their ego or sense of security).

In the next section you will learn ways to optimize the quality of your business.